Essay

Cybersecurity Superstition

- 1822 words

- –

Fear of hacking often conjures up images of a solitary figure cloaked in darkness, sporting a hoodie, and surrounded by monitors cascading Matrix style green code. Bonus points if the ‘hacker’ is wearing a Guy Fawkes mask. However, this depiction couldn’t be further from the truth. Most of the hackers I know either wear thigh high pink socks or are balding and middle aged.

Such misconceptions about hackers and cybersecurity in general have persisted for years, fuelled by sensationalism and misinformation. As someone frequently tasked with debunking cybersecurity fallacies, I’ve decided enough is enough. This article seeks to debunk common myths surrounding cybersecurity and, with any luck, also frees me from the perpetual cycle of explanation.

Note

This article is written with the average computer user in mind. In its suggestions, it targets both security and convenience. If you boast more technical expertise, then you can and should tweak this information to your needs.

Passwords

Almost everyone uses passwords. They’re the simplest solution for restricting access to something, and they do their job well. Unfortunately, years of bad advice has left people creating passwords that are confusing and insecure. I want to clear this up and identify some best practices.

Something to understand is that we generally calculate the strength of passwords using something called entropy. Entropy refers to how unpredictable something is - in this case, a password. We measure entropy in bits. The more bits of entropy a password has, the more guesses are needed to get it right.

A short password is easy to guess, but as you might imagine, it becomes harder to guess the longer it becomes. The act of guessing passwords through this guess work is called bruteforcing.

Bruteforcing is when someone tries lots of different passwords in rapid succession to find the one that works. A bit like when you get locked out of your phone and try lots of different variations in an attempt to rediscover your password.

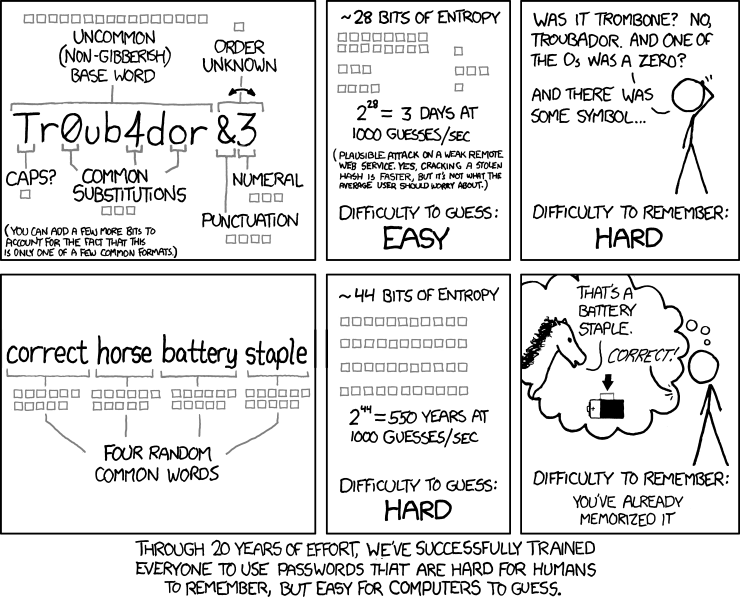

Most people know not to use names or common phrases in their passwords. Through years of conditioning, we’ve taught people that they should construct confusing passwords, substituting letters for numbers and forcing in random characters as they please. The embedded xkcd comic outlines the issue.

These confusing, special character infused passwords don’t improve security; they harm it. They are hard for humans and easy for computers - the worst of both worlds. I previously mentioned entropy and how we can use it to calculate the strength of a password. Well, it isn’t a perfect measure.

While bruteforcing may have started by simply crawling through a list of predefined common passwords, they later moved on to using complex algorithms. zxcvbn is a very useful tool that takes these algorithms into account to give an accurate idea of what more modern bruteforcing attacks are capable of.

Bitwarder is a free and open source password manager and supplies a free tool to check the strength of a password against zxcvbn. It’s worth giving it a go with a range of different passwords, just to see what is actually strong.

You should quickly come to realise that, for the average person, passphrases are much more effective than passwords. Easy to remember and, when done right, hard for a computer to crack.

Many people get this far and then make a fatal mistake. They reuse their passwords across multiple sites or store them insecurely. In the modern age, you should be using a password manager. Something like Bitwarden or Proton Pass allows you to generate secure passwords, store them, and auto fill them on the login page. It’s easy to use and provides much needed security. If you take one thing out of this article, make it this.

Periodic Password Changes

While I’m on the topic of passwords, I need to do a brief rant on mandatory password updates. Many organisations require that users periodically change their passwords. This is a terrible idea. Even Microsoft is against it.

It prevents users from memorising their passwords, and prompts them to create simpler, easier to remember passwords. It also results in security fatigue, where users become indifferent or careless about security measures in general, which undermines security measures.

Moreover, it also introduces unnecessary risk when users are forced to change their passwords, potentially leading to weaker passwords being chosen and opens up opportunities for phishing attacks.

There really is no point in implementing these forced changes, especially in the modern age. It does far more harm than good.

Multifactor Authentication

Some people think that a secure password is enough and that it’ll ensure their security, but passwords should only ever be used alongside another form of authentication. We call this Multifactor Authentication (MFA). Passwords aren’t perfect, and shouldn’t be the only point of access. It’s a single point of failure that can do undue and preventable damage.

Timed One Time Passwords (TOTP) are excellent and are one of the best options. The user receives a unique and temporary code that they can use. It’s easy for the user and extremely secure.

Unfortunately, one of the most common MFA solutions is SMS based authentication. It’s hugely insecure, and most advisories urge against its usage. Exploitation of the system is all too common, and I have an upcoming article discussing the inherent issues with SMS as a whole.

Another good option is hardware authentication, such as a Yubikey. This works as you might expect a car or house key to function. You plug it into your computer, and it authenticates you. Unfortunately, this also introduces issues of its own. One of these issues is the potential for loss or theft of the physical device. The effect is more or less the same as what would happen should keys of any other nature be lost or stolen.

Social Engineering

The fact that focus is often on concepts such as making secure passwords, encryption, and obscurity is detrimental to awareness of the real threat. Social engineering. It is far easier for a malicious actor to put together a simple attack that exploits human nature than it is to sink time into finding software vulnerabilities to exploit.

I think the best example I can give is this scene from the 1995 film Hackers. The movie as a whole has aged and definitely has its flaws, but I think this perfectly encapsulates how social engineering works.

This scene illustrates how simple and innocuous a good social engineering attack can appear, yet how effective it can be. Something akin to this is the most significant and prevalent threat.

It highlights all the hallmarks of a good social engineering attack. A convincing story, a sense of urgency, and an overwhelming of the victim. They all come together to help the hacker achieve what they want without the need for any messy script writing.

Social engineering is the most common vector of attack, not traditional ‘hacking’ as the media might portray. While it’s important to have at least a basic security setup, that shouldn’t be your sole focus. Educate yourself on common social engineering tactics, notably phishing attacks, and maintain a vigilant stance online. Approach all interactions with a healthy dose of scepticism.

Antiviruses

Something I despise and am long overdue to talk about is the fearmongering of antivirus companies. In the modern age, the average consumer does not need to go out of their way to install an antivirus on their device. Despite this, companies will use scare tactics to extort money out of users who know no better.

Most laptops and desktop computers run Windows, which is a malware mess. That said, I still don’t recommend going out of your way to install an antivirus, as the Microsoft Defender, which is directly integrated into Windows, is remarkably capable. Just open it up and check that it’s working at full capacity, and ensure you use Windows Update regularly to keep the definitions at the latest versions.

Unlike computers, phones operate in a closed ecosystem. Apps are screened for malicious content before being added to app stores. That makes it hard to install malware in the first place. Apps are also usually sandboxed, which stops them from interacting with the system at large and prevents anything that may be malicious from doing any real damage.

This doesn’t mean it’s impossible for phones to be hacked, but it does mean that it’s a lot harder for it to happen unless you do things outside the norm. It’s still possible to encounter malware on phones, but an antivirus really isn’t necessary and will likely do more harm than good.

While it’s not worth going out of your way to install an antivirus in the majority of cases, it is worth installing an ad blocker. I’d recommend uBlock Origin, which is free, open source, and supported on most of the major browsers. uBlock Origin doesn’t just block ads; it also blocks a lot of phishing material and malware links. Even America’s FBI recommend using an adblocker.

IP Addresses

One aspect of cybersecurity that often garners outsized concern is the IP address. As the name suggests, it serves as an address, pinpointing the location of a device or a network within the vast expanse of the internet.

A private IP address identifies a device on a network, while a public IP address signifies a network within the internet. With an IP address, you can glean information such as the ISP that assigned it, a vague geographical location, and some miscellaneous details. However, this information typically lacks significant personal identification.

This doesn’t mean it isn’t possible to use somebody’s IP maliciously, though. For instance, someone could attempt to launch a Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attack to disrupt your network. Unless you’ve compromised your router’s security by creating vulnerabilities in your firewall, the potential damage of most attacks is largely mitigated.

Also, IP addresses are not static; they change periodically. Most consumers have dynamic public IP addresses, meaning their ISP will routinely alter them every few weeks or so.

Unless you’ve really gone out of your way to make an enemy, and have poked holes through all the prequipped security, someone knowing your IP isn’t a huge security threat, although it is worth assessing it as a potential privacy threat.

VPNs

In the same vein as antiviruses, many Virtual Private Network (VPN) operators employ the same scare tactics and fearmongering regarding issues that haven’t been relevant for years.

They especially advertise that they can mask users IPs, which, as discussed previously, isn’t as important for most people as it may seem. Even if it were hugely important, it just means that your IP is being sent to them instead of elsewhere.

There is much more to be said about VPNs, but nothing that isn’t better covered by Tom Scott’s excellent video, This Video Is Sponsored By ███ VPN.